Redux is fantastic.

Some of you might disagree, so let me tell you why.

Over the last few years, Redux has popularized the idea of using message-passing (also known as event-driven programming) to manage application state. Instead of making arbitrary method calls to various class instances or mutating data structures, we now can think of state as being in a "predictable container" that only changes as a reaction to these "events".

This simple idea and implementation is universal enough to be used with any framework (or no framework at all), and has inspired libraries for other popular frameworks such as:

However, Redux has recently come under scrutiny by some prominent developers in the web community:

If you don't know these developers, they are the co-creators of Redux themselves. So why have Dan and Andrew, and many other developers, all but forsaken the use of Redux in applications?

The ideas and patterns in Redux appear sound and reasonable, and Redux is still used in many large-scale production apps today. However, it forces a certain architecture in your application:

As it turns out, this kind of single-atom immutable architecture is not natural nor does it represent how any software application works (nor should work) in the real-world.

Redux is an alternative implementation of Facebook's Flux "pattern". Many sticking points and hardships with Facebook's implementation have led developers to seek out alternative, nicer, more developer-friendly APIs such as Redux, Alt, Reflux, Flummox, and many more.. Redux emerged as a clear winner, and it is stated that Redux combines the ideas from:

However, not even the Elm architecture is a standalone architecture/pattern, as it is based on fundamental patterns, whether developers know it or not:

Rather than someone inventing it, early Elm programmers kept discovering the same basic patterns in their code. It was kind of spooky to see people ending up with well-architected code without planning ahead!

In this post, I will highlight some of the reasons that Redux is not a standalone pattern by comparing it to a fundamental, well-established pattern: the finite state machine. This is not an arbitrary choice; every single application that we write is basically a state machine, whether we know it or not. The difference is that the state machines we write are implicitly defined.

I hope that some of these comparisons and differences will help you realize how some of the common pain points in Redux-driven applications materialize, and how you can use this existing pattern to help you craft a better state management architecture, whether you're using Redux, another library, or no library at all.

What is a finite state machine?

(Taken from another article I wrote, The FaceTime Bug and the Dangers of Implicit State Machines):

Wikipedia has a useful but technical description on what a finite state machine is. In essence, a finite state machine is a computational model centered around states, events, and transitions between states. To make it simpler, think of it this way:

- Any software you make can be described in a finite number of states (e.g.,

idle,loading,success,error) - You can only be in one of those states at any given time (e.g., you can’t be in the

successanderrorstates at the same time) - You always start at some initial state (e.g.,

idle) - You move from state to state, or transition, based on events (e.g., from the

idlestate, when theLOADevent occurs, you immediately transition to theloadingstate)

It’s like the software that you’re used to writing, but with more explicit rules. You might have been used to writing isLoading or isSuccess as Boolean flags before, but state machines make it so that you’re not allowed to have isLoading === true && isSuccess === true at the same time.

It also makes it visually clear that event handlers can only do one main thing: forward their events to a state machine. They’re not allowed to “escape” the state machine and execute business logic, just like real-world physical devices: buttons on calculators or ATMs don’t actually do operations or execute actions; rather, they send "signals" to some central unit that manages (or orchestrates) state, and that unit decides what should happen when it receives that "signal".

What about state that is not finite?

With state machines, especially UML state machines (a.k.a. statecharts), "state" refers to something different than the data that doesn't fit neatly into finite states, but both "state" and what's known as "extended state" work together.

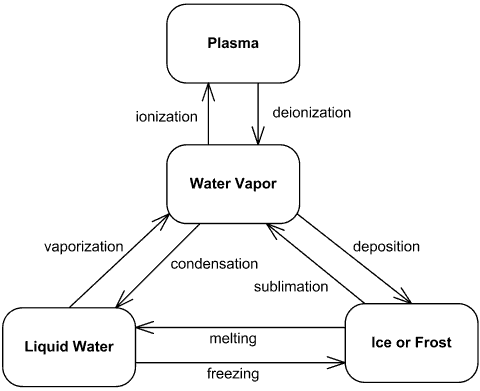

For example, let's consider water 🚰. It can fit into one of four phases, and we consider these the states of water:

liquidsolid(e.g., ice, frost)gas(e.g., vapor, steam)plasma

Water phase UML state machine diagram from uml-diagrams.com

However, the temperature of water is a continuous measurement, not a discrete one, and it can't be represented in a finite way. Despite this, water temperature can be represented alongside the finite state of water, e.g.:

liquidwheretemperature === 90(celsius)solidwheretemperature === -5gaswheretemperature === 500

There's many ways to represent the combination of finite and extended state in your application. For the water example, I would personally call the finite state value (as in the "finite state value") and the extended state context (as in "contextual data"):

const waterState = {

value: 'liquid', // finite state

context: {

// extended state

temperature: 90,

},

};

But you're free to represent it in other ways:

const waterState = {

phase: 'liquid', // finite state

data: {

// extended state

temperature: 90,

},

};

// or...

const waterState = {

status: 'liquid', // finite state

temperature: 90, // anything not 'status' is extended state

};

The key point is that there is a clear distinction between finite and extended state, and there is logic that prevents the application from reaching an impossible state, e.g.:

const waterState = {

isLiquid: true,

isGas: true, // 🚱 Water can't be both liquid and gas simultaneously!

temperature: -50, // ❄️ This is ice!! What's going on??

};

And we can extend these examples to realistic code, such as changing this:

const userState = {

isLoading: true,

isSuccess: false,

user: null,

error: null,

};

To something like this:

const userState = {

status: 'loading', // or 'idle' or 'error' or 'success'

user: null,

error: null,

};

This prevents impossible states like userState.isLoading === true and userState.isSuccess === true happening simultaneously.

How does Redux compare to a finite state machine?

The reason I'm comparing Redux to a state machine is because, from a birds-eye view, their state management models look pretty similar. For Redux:

state+action=newState

For state machines:

state+event=newState+effects

In code, these can even be represented the same way, by using a reducer:

function userReducer(state, event) {

// Return the next state, which is

// determined based on the current `state`

// and the received `event` object

// This nextState may contain a "finite"

// state value, as well as "extended"

// state values.

// It may also contain side-effects

// to be executed by some interpreter.

return nextState;

}

There are already some subtle differences, such as "action" vs. "event" or how extended state machines model side-effects (they do). Dan Abramov even recognizes some of the differences:

A reducer can be used to implement a finite state machine, but most reducers are not modeled as finite state machines. Let's change that by learning some of the differences between Redux and state machines.

Difference: finite & extended states

Typically, a Redux reducer's state will not make a clear distinction between "finite" and "extended" states, as previously mentioned above. This is an important concept in state machines: an application is always in exactly one of a finite number of "states", and the rest of its data is represented as its extended state.

Finite states can be introduced to a reducer by making an explicit property that represents exactly one of the many possible states:

const initialUserState = {

status: 'idle', // explicit finite state

user: null,

error: null,

};

What's great about this is that, if you're using TypeScript, you can take advantage of using discriminated unions to make impossible states impossible:

interface User {

name: string;

avatar: string;

}

type UserState =

| { status: 'idle', user: null, error: null }

| { status: 'loading', user: null, error: null }

| { status: 'success', user: User, error: null }

| { status: 'failure', user: null, error: string };

Difference: events vs. actions

In state machine terminology, an "action" is a side-effect that occurs as the result of a transition:

When an event instance is dispatched, the state machine responds by performing actions, such as changing a variable, performing I/O, invoking a function, generating another event instance, or changing to another state.

This isn't the only reason that using the term "action" to describe something that causes a state transition is confusing; "action" also suggests something that needs to be done (i.e., a command), rather than something that just happened (i.e., an event).

So keep the following terminology in mind when we talk about state machines:

- An event describes something that occurred. Events trigger state transitions.

- An action describes a side-effect that should occur as a response to a state transition.

The Redux style guide also directly suggests modeling actions as events:

However, we recommend trying to treat actions more as "describing events that occurred", rather than "setters". Treating actions as "events" generally leads to more meaningful action names, fewer total actions being dispatched, and a more meaningful action log history.

Source: Redux style guide: Model actions as events, not setters

When the word "event" is used in this article, that has the same meaning as a conventional Redux action object. For side-effects, the word "effect" will be used.

Difference: explicit transitions

Another fundamental part of how state machines work are transitions. A transition describes how one finite state transitions to another finite state due to an event. This can be represented using boxes and arrows:

This diagram makes it clear that it's impossible to transition directly from, e.g., idle to success or from success to error. There are clear sequences of events that need to occur to transition from one state to another.

However, the way that developers tend to model reducers is by determining the next state solely on the received event:

function userReducer(state, event) {

switch (event.type) {

case 'FETCH':

// go to some 'loading' state

case 'RESOLVE':

// go to some 'success' state

case 'REJECT':

// go to some 'error' state

default:

return state;

}

}

The problem with managing state this way is that it does not prevent impossible transitions. Have you ever seen a screen that briefly displays an error, and then shows some success view? If you haven't, browse Reddit, and do the following steps:

- Search for anything.

- Click on the "Posts" tab while the search is happening.

- Say "aha!" and wait a couple seconds.

In step 3, you'll probably see something like this (visible at the time of publishing this article):

After a couple seconds, this unexpected view will disappear and you will finally see search results. This bug has been present for a while, and even though it's innocuous, it's not the best user experience, and it can definitely be considered faulty logic.

However it is implemented (Reddit does use Redux...), something is definitely wrong: an impossible state transition happened. It makes absolutely no sense to transition directly from the "error" view to the "success" view, and in this case, the user shouldn't see an "error" view anyway because it's not an error; it's still loading!

You might be looking through your existing Redux reducers and realize where this potential bug may surface, because by basing state transitions only on events, these impossible transitions become possible to occur. Sprinkling if-statements all over your reducer might alleviate the symptoms of this:

function userReducer(state, event) {

switch (event.type) {

case 'FETCH':

if (state.status !== 'loading') {

// go to some 'loading' state...

// but ONLY if we're not already loading

}

// ...

}

}

But that only makes your state logic harder to follow because the state transitions are not explicit. Even though it might be a little more verbose, it's better to determine the next state based on both the current finite state and the event, rather than just on the event:

function userReducer(state, event) {

switch (state.status) {

case 'idle':

switch (event.type) {

case 'FETCH':

// go to some 'loading' state

// ...

}

// ...

}

}

You can even split this up into individual "finite state" reducers, to make things cleaner:

function idleUserReducer(state, event) {

switch (event.type) {

case 'FETCH':

// go to some 'loading' state

// ...

}

default:

return state;

}

}

function userReducer(state, event) {

switch (state.status) {

case 'idle':

return idleUserReducer(state, event);

// ...

}

}

But don't just take my word for it. The Redux style guide also strongly recommends treating your reducers as state machines:

[...] treat reducers as "state machines", where the combination of both the current state and the dispatched action determines whether a new state value is actually calculated, not just the action itself unconditionally.

I also talk about this idea in length in my post: No, disabling a button is not app logic.

Difference: declarative effects

If you look at Redux in isolation, its strategy for managing and executing side-effects is this:

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

That's right; Redux has no built-in way of handling side-effects. In any non-trivial application, you will have side-effects if you want to do anything useful, such as make a network request or kick off some sort of async process. Importantly enough, side-effects should not be considered an afterthought; they should be treated as a first-class citizen and uncompromisingly represented in your application logic.

Unfortunately, with Redux, they are, and the only solution is to use middleware, which is inexplicably an advanced topic, despite being required for any non-trivial app logic:

Without middleware, Redux store only supports synchronous data flow.

Source: Redux docs: Async Flow

With extended/UML state machines (also known as statecharts), these side-effects are known as actions (and will be referred to as actions for the rest of this post) and are declaratively modeled. Actions are the direct result of a transition:

When an event instance is dispatched, the state machine responds by performing actions, such as changing a variable, performing I/O, invoking a function, generating another event instance, or changing to another state.

_Source: (Wikipedia) UML State Machine: Actions and Transitions

This means that when an event changes state, actions (effects) may be executed as a result, even if the state stays the same (known as a "self-transition"). Just like Newton said:

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Source: Newton's Third Law of Motion

Actions never occur spontaneously, without cause; not in software, not in hardware, not in real life, never. There is always a cause for an action to occur, and with state machines, that cause is a state transition, due to a received event.

Statecharts distinguish how actions are determined in three possible ways:

- Entry actions are effects that are executed whenever a specific finite state is entered

- Exit actions are effects that are executed whenever a specific finite state is exited

- Transition actions are effects that are executed whenever a specific transition between two finite states is taken.

Fun fact: this is why statecharts are said to have the characteristic of both Mealy machines and Moore machines:

- With Mealy machines, "output" (actions) depends on the state and the event (transition actions)

- With Moore machines, "output" (actions) depends on just the state (entry & exit actions)

The original philosophy of Redux is that it did not want to be opinionated on how these side-effects are executed, which is why middleware such as redux-thunk and redux-promise exist. These libraries work around the fact that Redux is side-effect-agnostic by having third-party, use-case specific "solutions" for handling different types of effects.

So how can this be solved? It may seem weird, but just like you can use a property to specify finite state, you can also use a property to specify actions that should be executed in a declarative way:

// ...

case 'FETCH':

return {

...state,

// finite state

status: 'loading',

// actions (effects) to execute

actions: [

{ type: 'fetchUser', id: 42 }

]

}

// ...

Now, your reducer will return useful information that answers the question, "what side-effects (actions) should be executed as a result of this state transition?" The answer is clear and colocated right in your app state: read the actions property for a declarative description of the actions to be executed, and execute them:

// pretend the state came from a Redux React hook

const { actions } = state;

useEffect(() => {

actions.forEach((action) => {

if (action.type === 'fetchUser') {

fetch(`/api/user/${action.id}`)

.then((res) => res.json())

.then((data) => {

dispatch({ type: 'RESOLVE', user: data });

});

}

// ... etc. for other action implementations

});

}, [actions]);

Having side-effects modeled declaratively in some state.actions property (or similar) has some great benefits, such as in predicting/testing or being able to trace when actions will or have been executed, as well as being able to customize the implementation details of executing those actions. For instance, the fetchUser action can be changed to read from a cache instead, all without changing any of the logic in the reducer.

Difference: sync vs. async data flow

The fact is that middleware is indirection. It fragments your application logic by having it present in multiple places (the reducers and the middleware) without a clear, cohesive understanding of how they work together. Furthermore, it makes some use-cases easier but others much more difficult. For example: take this example from the Redux advanced tutorial, which uses redux-thunk to allow dispatching a "thunk" for making an async request:

function fetchPosts(subreddit) {

return (dispatch) => {

dispatch(requestPosts(subreddit));

return fetch(`https://www.reddit.com/r/${subreddit}.json`)

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((json) => dispatch(receivePosts(subreddit, json)));

};

}

Now ask yourself: how can I cancel this request? With redux-thunk, it simply isn't possible. And if your answer is to "choose a different middleware", you just validated the previous point. Modeling logic should not be a question of which middleware you choose, and middleware shouldn't even be part of the state modeling process.

As previously mentioned, the only way to model async data flow with Redux is by using middleware. And with all the possible use-cases, from thunks to Promises to sagas (generators) to epics (observables) and more, the ecosystem has plenty of different solutions for these. But the ideal number of solutions is one: the solution provided by the pattern in use.

Alright, so how do state machines solve the async data flow problem?

They don't.

To clarify, state machines do not distinguish between sync and async data flows, because there is no difference. This is such an important realization to make, because not only does it simplify the idea of data flow, but it also models how things work in real life:

- A state transition (triggered by a received event) always occurs in "zero-time"; that is, states synchronously transition.

- Events can be received at any time.

There is no such thing as an asynchronous transition. For example, modeling data fetching doesn't look like this:

idle . . . . . . . . . . . . success

Instead, it looks like this:

idle --(FETCH)--> loading --(RESOLVE)--> success

Everything is the result of some event triggering a state transition. Middleware obscures this fact. If you're curious how async cancellation can be handled in a synchronous state transition manner, here's a couple of guiding points for a potential implementation:

- A cancellation intent is an event (e.g.,

{ type: 'CANCEL' }) - Cancelling an in-flight request is an action (i.e., side-effect)

- "Canceled" is a state, whether it's a specific state (e.g.,

canceled) or a state where a request shouldn't be active (e.g.,idle)

To be continued

It is possible to model application state in Redux to be more like a finite state machine, and it is good to do so for many reasons. The applications that we write have different modes, or "behaviors", that vary depending on which "state" it's in. Before, this state might have been implicit. But now, with finite states, you can group behavior by these finite states (such as idle, loading, success, etc.), which makes the overall app logic much more clear, and prevents the app from getting stuck in an impossible state.

Finite states also make clear what events can do, depending on which state it's in, as well as what all the possible states are in an application. Additionally, they can map one-to-one to views in user interfaces.

But most importantly, state machines are present in all of the software that you write, and they have been for over half a century. Making finite state machines explicit brings clarity and robustness to complex app logic, and it is possible to implement them in any libraries that you use (or even no library at all).

In the next post, we'll talk about how the Redux atomic global store is also half of a pattern, the challenges it presents, and how it compares to another well-known model of computation (the Actor model).